31 August 2023

The diffusion of innovation curve - and its impact on go-to-market

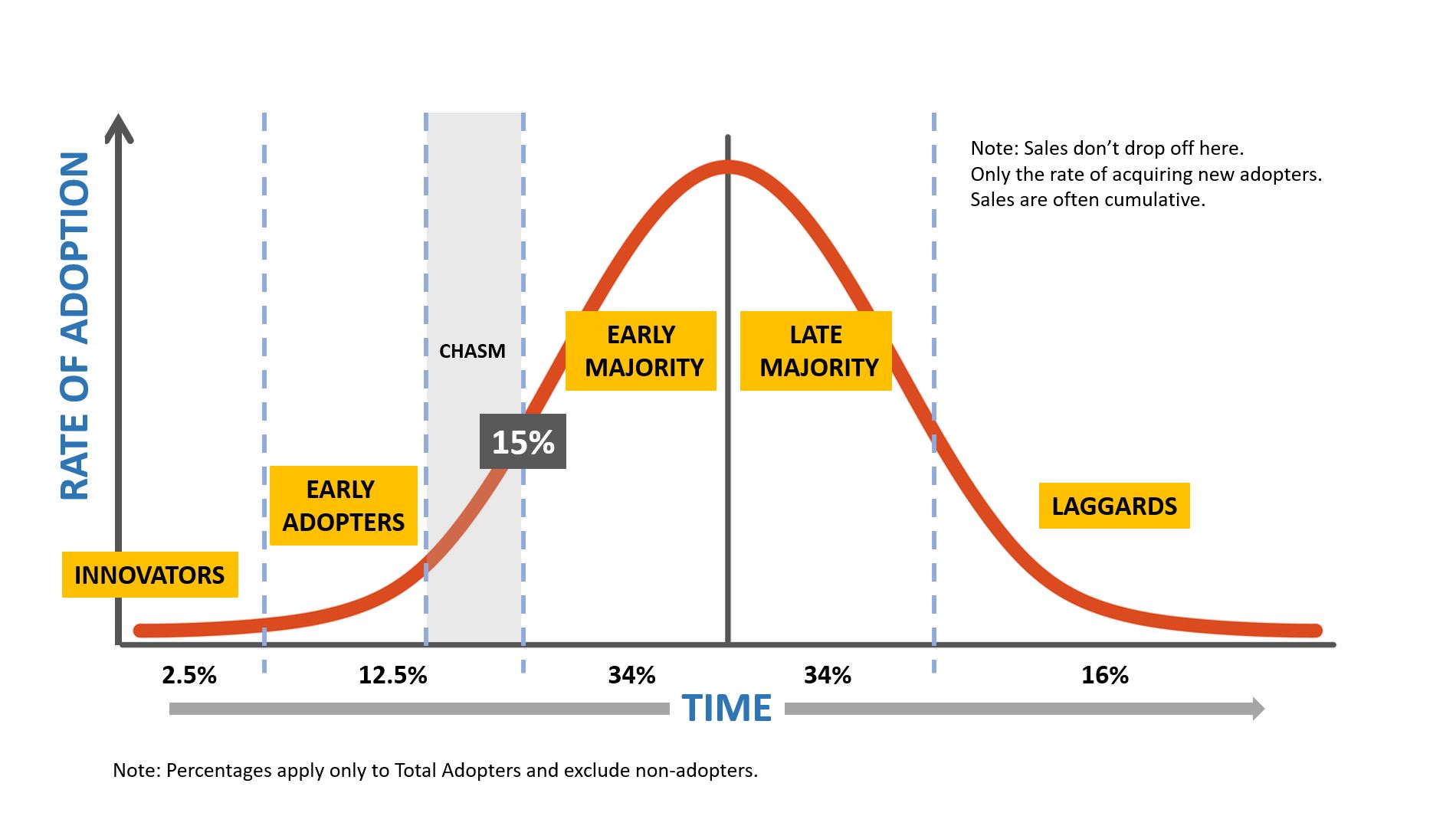

Diffusion of Innovation models the adoption of a new technology, concept, fashion, or product noting some people adopt earlier than others, but most people will not adopt until they see others go first. The implications are that speed to market and efficiency can be improved by first targeting the earlier adopters (if it is possible to identify them and selectively target).

The type of messaging, targeting, and promotion strategy needed to sell to early adopters is usually quite different to what's needed to sell to people in the later stages of the adoption cycle.

This can be critical in B2B markets where there is high value in establishing reference sites and/or case studies.

The rate of adoption is described by the following curve...

While not useful only for marketing, the Product Lifecycle diffusion curve is a fundamental marketing concept; consumers or customers vary in their risk appetite and propensity to adopt a new product or innovation.

The implications for any go-to-market process are profound; targeting needs to match the mindset of people depnding where they sit on the curve or risk severely impeding the rate of market penetration (sales growth). Or worse, risk product failure.

As the names on the curve suggest (INNOVATORS through to LAGGARDS) the people at the start of the curve try the product first before those at the end of the curve. The question is why? What makes them different?

A key principle of Diffusion of Innovation is that the majority of people need to see others using the product FIRST before they will try it.

The marketing approach needs to be calibrated to the different types of people in the innovation curve.

Crossing the chasm

When launching a new product or innovation, the critical step is moving from those that adopt the new product first (or new innovation) and into the middle majority which comprise roughly 2/3rds of the available market. The EARLY MAJORITY and LATE MAJORITY are known as the mass-market.

This step from the INNOVATORS and EARLY ADOPTERS into the mass market was dubbed "Crossing the Chasm" first proposed in a book of the same name by Geoffrey Moore published in 1991.

In order to achieve product-market fit, we must start with the early adopters. If you can’t find EARLY ADOPTERS it is unlikely that you will ever achieve product-market fit.

As Geoffrey Moore put it "To light a billion-dollar bonfire. You don’t hold your match under a big log, you light the kindling first."

Origins of the diffusion of innovation theory

Bryce Ryan and Neal Gross 1943: "Non-economic influencers on farmer’s economic decisions."

The diffusion of innovation theory was first proposed by Everett Rogers based on the ground work of Bryce Ryan and Neal Gross in 1943 who studied the adoption of Hybrid Corn seed in two Iowa (United States) communities (Stanton and Jefferson in Iowa). A seed manufacturer had developed a new breed of corn (an Innovation) that had significant superiority over the standard corn seed being used by farmers at the time.

'Hybrid Corn' increased yields by on average 20%. It was a no-brainer.

But it took 13 years to achieve 100% adoption. Ryan and Gross were curious to find out why, and posed the question "what was the difference between farmers who were first to adopt and those who were last?" They interviewed 259 farmers in two Iowa communities.

The core concept of the study was "non-economic factors on economic decisions." The study proponents had hypothesized that since the new seed would clearly deliver significant improvement in yields (and therefore farmer's income) that the decision about when and if to try the new seed must have been based on more that just economic factors.

In 1954 Everett Rogers (who grew-up on an Iowa farm nearby), came across the study (and other diffusion studies based on adoption of Weed Spray and a medical study on the take-up of a new antibiotic called Tetracycline). This work was incorporated into his own dissertation study thus leading to a general model of diffusion. At the time the model was not seen as a marketing specific topic, and to this day is applied to a wide range of innovation ranging from teaching gay men how to practice safe-sex (to slow the spread of aids in the 80's) to the inculcation of political ideas.

Everett Rogers published his first book "Diffusion of Innovations" in 1962 that was the beginning of a "general model of Innovation." Since then, there have been literally thousands of books published on the topic. Diffusion research continues with roughly 120 new publications every year.

Understanding the diffusion of innovation curve

The diffusion curve is not an infallible smooth curve that plays out exactly, but a good model...

It's not a sales volume curve: The first mistake people make when looking at the diffusion of innovation curve is to think that it is modelling sales volumes, that as the curve rolls off at the top, sales decline with the downward slope. This is not the case. It's an adoption curve. That is, it shows the rate at which new customers are becoming users of the product. Therefore, for products that commonly experience repeat purchases, sales volumes will be cumulative.

It's not applicable to the total population: The rate of adoption only applies to people who become users. 100% market share in any product category is highly unlikely. The curve excludes non-adopters.

The curve is a hypothetical model: of the underlying principal (rate of adoption) but rarely will the rate of adoption track a smooth curve. During the product lifecycle, a competitor may enter the market, or change the competitive dynamics. Similarly, the company may alter its tactics. The economy may change.

Case by case: In general, people who adopt early compared to those who take their time exhibit that behavior consistently; it's a personality thing. However, you can't always make this assumption. Innovations need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Somebody may immediately see the benefits of a new technology applicable to their industry and adopt straight away, but couldn't care less about buying the latest iPhone.

Diffusion of innovation - categories of people in a social system

Innovation adoption theory refers to people (described by the model) as being part of a social group. In marketing, we call these social groups "target markets". However, innovation theory has broader application, hence the use of the term "social group" (like the corn farmers in the foundation research). Here are the defining features of the various categories in a social group with respect to their propensity to adopt an innovation.

Innovators: always the first to adopt new things because they are not just intrigued by new things, but because it defines who they are. More likely to take risks and like being on the cutting edge, they are important for introducing new ideas and products to the rest of the population because they like to share their experiences with others. Early success when launching a new product is often simply a case of putting the new product in front of them. However, satisfying INNOVATORS is usually not enough to achieve long term success because they comprise only about 2.5% of the potential market.

Early adopters: are also a forward-thinking group and are often highly respected and opinion leaders. Their endorsement of an innovation plays a key role in what is known as “crossing the chasm” which is when the adoption of an innovation crosses the gap between the trend setters and the rest of the population. What makes EARLY ADOPTERS different from INNOVATORS is that they see the competitive advantage that the new innovation may deliver whereas INNOVATORS just like being first.

This point cannot be stressed enough: the early adopters are the first to see the application of the innovation to the problem they are seeking to solve.

Their mindset and motivation is different to the innovators; they don't want to be FIRST for its own sake, they desire the advantage that the new innovation provides and the benefits that it will deliver. The emotional disposition is less vanity and more practicality. What makes them different is they are the first to understand the true value of the innovation and are willing to take the risk because the potential rewards to them are large.

This makes them incredibly important to the launch of new innovations because the Early Adopters become the example that encourages the middle majority to adopt. The greatest leverage occurs when the middle majority start to perceive they are losing traction to the early adopters and believe it is because they are not using the new innovation.

The next two groups are critical for the success of new innovations. Roughly 2/3 of the population fall into the middle majority. This is the mass market where volume sales are generated from.

The early majority: take time to make decisions. They will observe other’s experiences and will only adopt an innovation when they are convinced of the value proposition. They shy away from being first, and only feel comfortable when they see enough other people already using the product. They wait for the new status quo to be established and tend to make pragmatic decisions.

Late majority: are more resistant to change but are responsive to peer pressure. They want new innovations to be thoroughly tested and widely used before they risk trying.

Laggards: the last group to adopt new products or innovations. They are both highly resistant to change and are hard to reach with marketing campaigns often having minimal exposure to media. They will wait until new innovations or products are completely mainstream before they will adopt. In some cases, they never do. As a general principle, they only adopt innovations when it becomes a necessity (e.g. the old technology is no longer being manufactured).

Non-Adopters: A proportion of a social group may NEVER adopt an innovation. It is important to note that the percentages in the above adoption curve refer to the total number who eventually adopt rather than the total population of a social group. What makes NON-ADOPTERS special is, unlike the rest of the population, non-adopters could benefit from the innovation but never adopt. Failure to adopt may be due to not knowing about the innovation, not putting the effort into understanding it (not engaged - distracted by other things), not understanding it even when they tried, not seeing the value, can’t afford it, or something better comes along. This can be due to failures in the communication process, complexities within the social group, poor product concept or value proposition, or efforts by competitors.